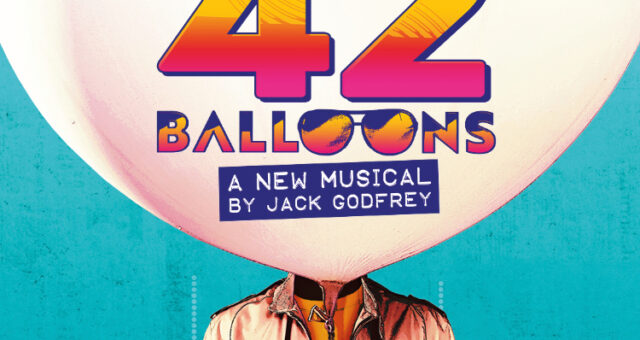

42 Balloons Day Out

Salford day out! Join MTN/MMD members and staff to watch the much anticipated new musical 42 Balloons by MMD member...

Read moreOur offer evolves through dialogue with what’s happening in that sector. Gathered here are the main recurring formats within which we share and develop content which strategically responds to opportunities and challenges in the UK’s new musical theatre landscape. We work in partnership with our members, funders and industry peers to make improvements, nurture useful connections, and advocate for best practice. We see diversifying musical theatre as fundamental to the art form’s development in the UK. That includes amplifying the voices of creatives from previously underrepresented backgrounds/identities, encouraging a broadening of music styles and theatrical approaches, and advocating improved inclusivity for all.

We co-produce the UK’s leading conference event considering the musical theatre sector and art form in the UK.

Learn more

The Mackintosh Foundation funds this scheme of resident musical theatre writer placements at producing venues across the UK.

Learn more

Partnering with China Plate, this is a residential talent development week for global majority musical theatre creatives.

Learn more

MTN hosts several peer-to-peer conversations each year, bringing industry representatives together to consider evolving best practice.

Learn more

Chaired panel discussions produced by MTN which bring together a diversity of relevant industry experts to share their insights.

Learn more

We often act as a first port of call for specialist advice or sector overview knowledge.

Learn more

Advocacy for the new musical theatre artform and sector is a central part of MTN’s mission.

Learn more

Salford day out! Join MTN/MMD members and staff to watch the much anticipated new musical 42 Balloons by MMD member...

Read more